CHAPTER VIII

November 12th.

What has happened ?

In front of one of the big schools sailors were lined up in a row. A company, armed to the teeth, stood in the middle of the road. People looked at each other curiously, anxiously. This school had an evil past. In October the deserters had gathered together here, the armed servants of the Károlyi revolution. It is said that Tisza's murderers started from this point.

" What are they up to now ? "

" They're Ladislaus Fényes's sailors. They're going to Pressburg against the Czechs, " a lean, fair man said.

Somebody sighed " Poor people of Pressburg ! " The fair man made a frightened sign to him to keep quiet. Behind his back an officer began to talk excitedly. I could only hear half of what he said, but it was something to the effect that in one of the barracks three thousand soldiers and five hundred officers who were going to the defence of Upper Hungary had been disarmed by the orders of Pogány.

A broad, dark Jew, rigged out in field uniform, now came out of the school building, a ribbon of national colours on his chest. His voice did not reach me. I only saw his mouth move. He addressed the sailors, and cheers rang through the street. The crowd rushed forward and I turned back to escape it, tried to reach home by a circuitous route. Suddenly I heard more cheering, and behind me the roadway resounded with heavy steps. The detachment of sailors was marching to the railway station, the mob accompanying it. The detachment was headed by the dark Jew, with drawn sword, and behind him marched a criminal looking rabble dressed in sailors' uniforms. Most of them wore red ribbons in their caps, and the deeply cut blouses displayed their bare, hairy chests. The last sailor was a squashed nosed, sturdy man, his dirty pimpled face shone. Round his bare neck he wore a red handkerchief. As he walked along he caught his foot in something and looked back. Between his strong, bushy eyebrows and protruding cheekbones his eyes were set deep. I shuddered. This riff-raff going to the defence of Pressburg ! Are such as they to recover Upper Hungary ?

Then I remembered. The man at the head of the sailors must have been Victor Heltai-Hoffer, who on the 31st of October, from the Hotel Astoria, was nominated Commander of Budapest's garrison. I was told that he had been a contractor, but people from Károlyi's entourage affirmed that he had been a waiter in a music-hall of ill-fame. Later he became a professional dancer, and during the war he lived by illicit trade, dabbling in hay, fat and sugar. Those who were his accomplices are not likely to be mistaken... On the day of the revolution Heltai offered to storm the Garrison's command with a band of deserters. This disgraceful success was followed by his nomination to the post of commander by Fényes, Kéri, and the other National councillors. A few days ago queer news was circulated about him, and he was suspended from his position. Heltai is said to be in possession of certain disgraceful secrets concerning those in power, and it was possible that he was put in command of the Pressburg relief force in order to get rid of him.

The noise of the sailors' steps was lost in the hubbub of the street. Carriages passed with their miserable lean horses, people went to and fro with spiritless monotony. Although the sailors had long disappeared I still seemed to see the last, with his squashed nose, his red tie. That criminal face wore the expression of the whole contingent.

And that horrible face under a cap worn on one side of the head is everywhere in a country that putrifies. It appears in the light of the burning houses, it enters at night into lonely manors, into cottages, it rushes in under the portals of palaces, goes through the rooms, searches, spies, and there is no escape from it. Whoever it pursues, it will catch... Then it wipes its bloody hands on silk or linen, and when its heavy step has passed, death grins in the dark, pillaged room behind it.

Once upon a time the word " sailor " brought to our minds the image of the great, free expanse of oceans and shores. Now we hold our breath at its sound, and shudder in horror.

That face with the sailor's cap worn rakishly on one side, that face with the deep, loot-seeking eyes... There it was in Moscow when thousands of Imperial officers were slaughtered between the walls of the Kremlin. It was in Petrograd in the hour of starkest horror, in Odessa, in Altona; and in Helsingfors it bathed itself in the blood of Finns. It is now in Berlin, in the Imperial castle on which the red flag floats. And it was lurking in the courtyard of Schonbrunn Castle when the Emperor Charles was driven from his home.

I can see the large staircase of Schonbrunn by which the Emperor, the Empress and their little fair children left their home, walking down alone, expelled. In olden days a hundred footmen jumped at a sign of their hand; courtiers bowed to the ground before them. Now, wherever they looked, there was not one faithful eye for them; whoever they might call, he would not come.

When Francis Joseph was dying on his little iron camp-bed, in a room at Schonbrunn, the heir to the crown and the Archduchess Zita wrung their hands in their despair. " Good God, not yet, not yet " ... Then the door of the old ruler's room was opened : it had become a mortuary, and they two walked slowly down the great gallery. The Court bowed low before them. And they walked weeping, holding each other's hands. Since then they have been always walking, through many mistakes, disappointments, and tears, and now they have reached the bottom of the staircase.

The little Crown Prince, as he had been taught, saluted all the time with his baby hands. " They won't acknowledge it to-day, mother, " he said sadly. The red-cockaded peoples' guards who occupied the place turned aside.

The King, in civilian clothes, with bowed head, stepped out into the open. The sound of his steps died away in the big, empty house, and the darkness of the evening swallowed up the garden, under whose straight-cut hedges, peopled with statues of gods and goddesses, the Hapsburgs had passed so many lovely summers.

When the royal motor-cars passed through the court of honour the usual bugle-call did not resound; the guard did not turn out, and red flags rose above the roofs of the houses of Schonbrunn. Over the gate the double-headed eagle was covered with red rags; though it had been predatory and had cruelly clawed peoples and countries, it had never returned from its flight without bringing treasures for Vienna. And it may be the greatest tragedy of the Hapsburgs that their unduly favoured capital turned indifferently away from them when the scum of the red power had driven them from home.

The rapidly speeding car took the unfortunate prince to Eckhardsau, and henceforth he lived under the protection of the National Council of the Renners and Bauers. Who knows for how long ? Who knows what is in store for him.

........

November 13th.

Every day has its news, and the news has eagle's claws that tear the living flesh.

Behind the retreating Mackensen, Roumanians pour through the Transylvanian passes. The Serbians have occupied the Bánat and the Bácska. Temesvár and Zombor are in their hands. The Czechs are advancing towards Kassa and, after having robbed our land, they even want to rob the country of its coat of arms. They have stolen our three hills surmounted by a double cross and have assigned it as arms to Upper Hungary, which they have named Slovensko.

To-day Linder is going to sign in Belgrade the death-bearing armistice conditions. In Arad, Jászi is distributing our possessions to the Roumanians. Károlyi is intriguing to undermine the power of Mackensen, who, at the head of forty to fifty thousand men, is the only armed hope remaining in the midst of destruction. A deputation of magnates, all, without exception, patriotic, faithful lords, has, inconceivably, arrived at Eckhardsau, to ask the King for his resignation. It is more than one can bear.

The country is going through the horrors of decomposition while still alive ; its counterfeit head is rotting and its members falling off. And there is no silence in our distracting grief; the great decay is accompanied by revolting continuous applause. Those who cause the ruin applaud themselves. In the press, in their speeches, on their posters, in their writings : their applause drowns the groans of agony. The day begins with this abject applause, for it appears in the morning papers, and in the evening it follows us home and haunts our dreams; it tears our self-respect to shreds, for it is a perpetual reminder of our own impotence. The press with its foreign soul, which has enmeshed public opinion completely, now prostitutes the soul and language of Hungary; it has betrayed and sold us; it applauds our degradation, jeers and throws dirt at the nation which has given its partisans a home.

The chief writer of Budapest's Jewish literature, Alexander Bródy, has written an article in an evening paper about the German Emperor, of whom he used to speak, not so long ago, when he was still in power, as if he were a demi-god. Now he starts as follows : " One of the world's greatest criminals, Wilhelm Hohenzollern, has escaped from his country, and in Holland has begged his way into the castle of Count Bentinck. There he slept last night with about ten others, a trifling part of his accursed race, with his always smart red-faced (because always drunk) son, the wife of the latter, Cecilia, and with the Mother-Empress, that shapeless female of the human species. " And he ends up : " Moaning, sick, uncomfortable, the escaped Kaiser lies on his bed. And for the present the 'poor old man' only trembles for his life; they may spit into his face, they may put him on his bended knees—nothing matters so long as his life is granted. "

He who now writes like this is the master of those radical journalists who form the major part of the present government. That is the spirit which rules over the forum to-day. That is the tone which is assumed by those who claim to speak for the nation, which for nearly a thousand years has enjoyed the reputation of being the most chivalrous nation of Europe.

This article, however, roused Hungarian society even from its present torpor. Only the meanest kick the unfortunate. The paper received several thousand letters of protest, and many subscribers returned their copies. But what is the good of that ? The paper takes no notice of protests, and the shame of the cowardly notice, like many other disgraceful actions committed in our name, will recoil upon us, and we shall have to bear its disgrace.

How long must we suffer this ? Good, gracious God, how long will it last ?

There is no place we can look to for consolation. From the frontiers, narrowing round us every day, fugitive Hungarians are pouring in. On all the roads of the land despoiled and homeless people are in flight. Carts and coaches, pedestrians and herds of cattle mix on the highway, and the trains roll along, dragging cattle trucks filled with homeless humanity. Villages, whole towns in flight...

Maddened, with weeping eyes, half Hungary is escaping towards the capital which has betrayed it. And the heart-breaking wave of humanity is no longer an unknown crowd : familiar names are mentioned, and one perceives familiar faces. They are coming by day and by night, those who have no hearth, no clothes, not a scrap of food; and instead of their clean homes they have to beg for quarters in low inns, for fantastic prices, even if it is but for a single night...

Rain poured down in the street. A cold wind blew at the corners as I walked with a little parcel under my arm towards a small hotel on the boulevards. I got the news this morning : some dear, good people have arrived there, robbed of everything they possessed. The hotel was ill-ventilated and dirty. The lift did not work, and I climbed painfully up the dark stairs. Muddy footsteps had left their mark on the dirty, crumpled carpet. And the whole place was pervaded with a stench made up of kitchen smells and the pungent odour of some insecticide.

In the dusk of the third floor's corridor I could not distinguish the numbers of the rooms. I opened a door at haphazard. The air of the room met me like a filthy, corrupt breath. A Polish Jew in his gabardine was standing near the window and, swaying from the hip, was explaining something with an air of importance to a clean-shaven co-religionary, dressed in the English style. A few men stood in the middle of the room, and foreign banknotes tied in bundles lay on the table. They seemed to be Russian roubles. One man threw a newspaper over the table and came towards me. " What do you want ? " he asked, rather embarrassed, though he spoke threateningly.

" I made a mistake, " I said, and banged the door.

Behind the next door I found the friends for whom I was looking. The wintry darkness was lit up by an electric light near the bed, on which a pale little boy was lying. The other child was huddled up in a chair, swinging his legs wearily. Their father stood with his back to me, between the two wings of the curtain, and was gazing through the window into the November rain. The mother was sitting motionless near the little invalid; her two hands lay open in her lap, as if she had dropped everything. When she recognised me she did not say a word, but just nodded, and tears came to her eyes. Her husband turned back from the window. His face was a picture of rebelling despair. He clenched his fists, and, while he spoke, walked restlessly up and down the room.

" The Roumanians have taken everything we possessed; nothing is left, though we have worked hard all our lives. They robbed us in our very presence. We had to look on and could do nothing to prevent it. Then they drove us out of the house with this sick child. "

" What is the matter with it ? "

" Typhus, and yet they showed no mercy. "

The sick boy tossed his head from one side to the other and groaned in his sleep. His groans are not the only ones that the shabby gray walls had heard this year. Rooms that are never unoccupied, rooms like great stuffy cupboards that are crammed with humanity. Their complements arrive and are crammed into them, awaiting with trembling heart the hour when some new arrivals, able to pay more, will crowd them out again. Up and out on to the road again, to drag with them the horrible vision of their lost land, their destroyed home, through the great town which has squandered without mercy that which was theirs and now has no pity for them.

But there is also another drawer in the cupboard : that other room, the man in his gabardine, the clean shaven one, the foreign money on the table... No, these don't suffer. These have cortie to take possession of what is left of Hungary.

Through the influence of Trotski, Jews from Hungary who were prisoners of war, became in Russia the dreaded tyrants of lesser towns, the heads of directorates. The Soviet now sends these people back as its agents. Will the government prevent them from coming ? Will it arrest them ? Probably not. Many believe that during his stay in Switzerland Károlyi came to an agreement with the Bolsheviki and now abets the world-revolutionary aims of the Russian terror. Sinister tales circulate under the walls of the houses of Pest. What madness ! An agricultural country like Hungary is no soil for that seed. And yet... A few days ago an alarming rumour spread. In vain did the government attempt to suppress it. The news leaked out that as soon as it had come to power the government received a wireless message from the Russian Workers' and Soldiers' Council, who sent their fraternal greetings and promised that the Russian Soviet would send help and food if only the Hungarian proletariat would join it in its war against the Capitalism of the Allies. For, said the wireless : " The freeing of the toiling masses is possible only through a proletarian world-revolution. Unite, Hungarian proletarians ! Long live the world-revolution ! Long live the dictatorship of the proletariat ! Long live the world's Soviet-republic ! "

This message, kindled by the fire of class hatred, spread its sparks over the Russian swamps, over the Carpathians, and fell glowing into Károlyi's nefarious camp. Nobody trod on it to extinguish it, it was kept alive, in secret, among them. No wonder they are uneasy.

........

November 14th.

The days are getting shorter and shorter, and darkness comes earlier every day.

The lamp was lit on my table. Count Emil Dessewffy was telling me about his journey to Eckhardsau. Now and then he fixed his strong single-eyeglass into his orbit, then again he toyed with it between his long, thin fingers, as if it were a shining coin. He was obviously nervous; and he kept crossing and uncrossing his legs.

" Prince Nicolas Eszterházy, Baron Wlassics, Count Emil Széchényi and I went there. The Cardinal Primate declined at the last moment. "

" How could you bring yourselves to such a step ? "

" Our intention was to check Károlyi's machinations, to obtain the resignation of the King, and to persuade his Majesty to stand aside temporarily. At first the King wouldn't listen to reason. He said he had taken the oath to the Hungarian people ; if others wanted to break their oath towards him, let them arrange that with their conscience; he was not going to perjure himself. We explained to him that as he had already transferred, alas, his supreme command to Károlyi, he would safeguard the interests of poor Hungary and of the dynasty better by standing aside during the period of transition, than by hanging on obstinately to his formal right. By this he might frustrate the attempt of those who are fishing in troubled waters to force the nation to face the fait accompli of a deposition by violence. The King stamped his foot and declared several times that whatever might happen he would not stand aside. We explained the advantages of the step from various points of view, and at last made him understand that after the mistakes that had already been made, no other solution was possible. Wlassics edited the document, but we couldn't make a final draft because no foolscap paper could be found in the whole castle. We sent out for some paper. Then there was no ink, and we had to search for a pen. Time passed, and meanwhile the King went out shooting... "

" Went out shooting ! " The whole tragedy seemed to be becoming a burlesque.

" Yes, we were rather shocked, " said Dessewffy. " But later on we found that there was not a scrap of food in the castle, and the King had to obtain game so that the Queen and the children might not starve. It is all very sad. Their clothes too were left behind in Vienna. When they left Schonbrunn they just threw a few things hurriedly into the car. The children have no change of clothes. They even had to sleep for several nights without bedclothes. It's no good sending messages to Vienna : the Government Council, which has taken them under its protection, does not even answer. "

I thought of the Austrian and Czech nobles, so favoured by the Hapsburgs, of those, who, insisting on their rights based on the Spanish etiquette of older times, were mortally offended if at some festivity at the Vienna Burg they could not stand in the immediate vicinity of the Emperor, or were put by mistake into a position somewhat inferior to their rank. Where were they ? Where was the ruler's General Staff ? The generals covered with orders ? Where was the bodyguard with its commander, which " dies but never surrenders ? " In the last days of Schonbrunn they all had withdrawn like the tide from the forsaken shore. " Nous étions tout seuls, " the Queen had said.

" And then ? " I asked Count Dessewffy.

" After a time some paper was brought, two sheets in all, and Széchényi sat down to make a clean copy of the document : he had the best handwriting of us all. "

Dessewffy showed me the original document. It read :

" Since the day of my succession to the throne I have always tried to free my people from the horrors of this war—a war in the causation of which I had no share whatever. I do not wish that my person should be an obstacle to the prosperity of the Hungarian people. Consequently I resign all participation in the direction of affairs of State and submit in advance to the decision by which Hungary will fix its future form of government. Dated at Eckhardsau, November 13th 1918.

Charles. "

" The King still hesitated when the document lay ready for signature on the table. And as he wavered with the pen in his hand he looked the very picture of despair. During the last few days the hair on the sides of his head has turned gray. Suddenly tears came into his eyes, and he fell sobbing on Count Hunyadi's shoulder. Well, none of our eyes were quite dry... "

While Dessewffy talked on, I thought of a tale I had heard long, long ago.

It was evening in a village far away. The autumnal wind was rising, and the poplars round the house were soughing like organ pipes in a dark church. In the kitchen the maids were shelling peas. The light of the fire played over their hands, and the dry shells fell with a gentle rattle on the brick floor. Katrin, the housekeeper, was telling a story... " And the wicked knights went into the King's tent, armed with halberds and maces, and said in a terrible voice : ' Give up your crown or you shall die the death.' The beautiful Queen folded her hands imploringly, and the King took his crown off his head... " That was the story. The maids cried over the poor king, and in their hearts approved of him.

In stories it is the unfortunate who are always right, in reality it is those on whom fortune smiles.

........

November 15th.

" Long live Michael Károlyi ! Elect him President of the Republic !... " Again a paper disease has infected the houses' skin.

In the first year of the war Michael Károlyi had betted that he would be the president of the Hungarian Republic... Will he win his bet tomorrow ? But whoever may win, Hungary will be the loser.

Posters... new posters appear above the old ones. A new shame covers the old, and that is all that changes in our lives. Big flags float in the wind on the boulevards. Flags are hoisted on the electric lamp-posts, and above the house entrances the old ones flap about. The government has ordered the beflagging of every house in the country, and its newspapers are preparing the mood of the morrow. They announce in big type :

THE RED FLAG HAS BEEN HOISTED IN THE FRENCH TRENCHES.

REVOLUTION HAS BROKEN OUT IN BELGIUM.

SWITZERLAND IS ON THE EVE OF A REVOLUTION.

I heard a little school-girl say to her friend : " Károlyi is a great man. He makes the fashion, now even the French are imitating us... "

" Long live... shouted the walls and the shop windows, but the people were silent. Why ? Why don't they tear down the disgraceful posters ? Why are they resigned, why do I alone protest ? Or are there more of us, only we don't know of each other ? I looked carefully at the passing faces. Their eyes passed indifferently over the posters. Nothing mattered to them. I walked quickly, as if haunted, a stranger among the soulless crowd.

I reached Károlyi's palace. The one-storeyed house, built in the Empire style, looked low under its old roof among the high, newly erected buildings. The row of windows was dark : Károlyi had already moved into the Prime Minister's house. The first floor was inhabited only by the tenant of half the building, Count Armin Mikes, and I had come to see his wife. Since the events of October I had not been there.

The little side gate opened as I rang, noiselessly, as if automatically, and the concierge looked out of his loge and disappeared. Nothing stirred. Under the deep arch of the entrance my steps alone resounded; they echoed strangely, as if invisible hands were dropping things behind me.

I stopped for an instant. The soul of the place seemed to be whispering in the dark. On the right side a corridor was visible through a glass-panelled door, its walls covered with revolutionary pictures, and at its end a side staircase led into Károlyi's apartments. I shuddered, as one does when one enters a house where a murder has been committed. The traitors—perjured officers, Gallileist students, deserters—congregated up there, in the dark rooms, in the nights of October. Those who sold us and, among themselves, sentenced Tisza to death whispered and advised up there.

I went on. From the semi-obscurity of the huge staircase, marble seemed to tumble down like a frozen waterfall. Beyond, in the garden, the trees whispered in the cold wind.

Countess Mikes' small drawing-room was light and warm. I found a gathering of Transylvanians there, and beyond the room the notorious house, the whole town, seemed to have disappeared. My own sufferings were forgotten in the recital of theirs, and I was no longer alone in my grief, for all who were present shared it with me. They helped to raise up hope, because they knew what patriotism was, it is an old legacy of theirs. The strength and the will power which supported Hungary throughout her most disastrous periods, when the Turks from the south and the Germans from the west trod on Hungary's soil, had their source in Transylvania. When the fire of resistance was extinguished everywhere else, it went on burning among its inhabitants. And so after every dark night our race has gone to Transylvania to kindle anew the flame which has lighted it back into the dying country.

Great, suffering Transylvania, what is thy reward for this ?

There they sat, Transylvanian men and women, the descendants of ancient princes, sufferers with shaded eyes. And as I looked at them there appeared behind their handsome faces the dreamlike outlines of a bluish-green landscape. As if seen in the crystal of an antique emerald ring, distant, dreamy trees appeared : two pointed poplars reached towards the sky : down below, among the meadows, a willow-bordered brook flowed softly : wagons rumbled on the winding road : a horseman came slowly, with a sack across the saddle in front of him. Beyond, the meadow rose to a velvety hillock, where an ancient spire, a little village, a tiny Székler village, nestled...

A wanderer told me the tale this summer, when I was in Transylvania. It happened during the war, in 1916. It was when the alarm was raised for the first time, and one day the cry passed through undefended Transylvania, " The Roumanians are coming ! " In mad haste it spread through the counties, rushed along the electric wires, rang in the bells : " Save yourselves ! " One village carried the next with it, Transylvania was fleeing.

In the village of Gelencze, on the bank of the rippling brook, at the foot of the hillock, there was silence. It was just like any other day; the people were working in the fields. Meanwhile the Roumanians crept cautiously through the undefended Transylvanian passes. One morning early, soon after the break of day, like some awful sudden death, they fell upon the people of Gelencze, there in their fields in the midst of their peaceful work. The people were helpless. Only one old Székler raised his spade, and fell with a shout among the rifles. They knocked him down, but he did not die; so they nailed him to a plank and dragged him into the forest that he might die there, alone. He was heard till nightfall, struggling and cursing the Roumanians.

That is how Gelencze was informed of the invasion of Transylvania. The alarm, the cry of warning, had passed it by, had missed it on the way. The telegraph wires carried the news, but they passed over its head, and not a word, not a sound came to bring warning. The Government, the County, the District, forgot—Hungary forgot the little village.

A wanderer told me all this, there, just outside the village of Gelencze, when it was still ours. And as I listened to the sad story it became bigger and deeper, so deep that the whole of Transylvania had room in it... The hillock became the mass of Transylvania's mountains, the brook became all Transylvania's rivers, and the fate of the village was Transylvania's fate.

" Do you remember how I promised you that summer, down there, that I would write a book of Transylvania, that I would trumpet the rights of your land, your race ? I was to proclaim the wrongs you have suffered and call to account those who directed Hungary's fate and for ever forgot the Hungarian folk in Transylvania. How they delivered you to the tender mercies of your foes, and armed neither your soul nor your arm for resistance... A forgotten village ! Do you remember ? I said that that should be the title of my book. You were nothing but a forgotten village to those who wielded power in Hungary. The sufferings of Transylvania never caused them a moment's inconvenience... And the present government surpasses them all. As if it had decided on your destruction it now sends out an old accomplice of the Roumanian Irredenta to speak in the defence of the victim whom he himself has condemned to death. Oscar Jászi deals to-day in Arad with Transylvania's fate."

Hate and disgust were depicted on the faces of the Transylvanian women. That man of Galician origin, the internationalist who wanted to make an eastern Switzerland of our country, and who hated everything that was Hungarian to such an extent that his hatred made him forget the traditional caution of his race and exclaim in a fury when speaking of us, " If they don't obey, let them be exterminated "—he is sent there to negotiate in the name of the Hungarian race ! The very spirit in which he conducted the negotiations showed his eagerness to revenge himself on the nation which had given him hospitality : he renounced what was not his, gave up rights which were ours, and sold Transylvania to Manin's Roumanian National Council, which he and Károlyi had themselves created during the October days. In Arad the Roumanians speak already of national sovereignty ! They claim a Roumanian supremacy and twenty-six Hungarian counties ! They demand that the Hungarian Popular Government shall disarm the police, disband the Hungarian National Guards, punish all energetic officers, but... that it shall provide arms for the Roumanian National Guards and pay for its men and officers out of the Hungarian taxpayer's pocket. Jászi and the revolutionary Government delegates have promised all this. Meanwhile the Roumanians are dragging out the negotiations, and their voices become more and more sharp and exacting, for do they not know that every hour takes the royal Roumanian troops deeper into the heart of undefended Transylvania ?

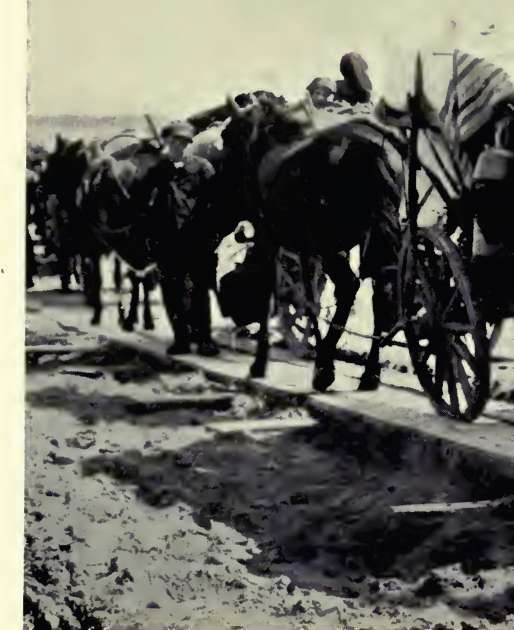

And while at the county hall of Arad the traitors are at work, the main column of Mackensen's always victorious army is rolling over the bridge across the Maros. Endless rows of motor columns pass. Behind them comes an unceasing flow of army service corps wagons, covered ammunition wagons, lorries, carts and waggonets. Hours and days pass, and they are still going on, orderly, gray, grave. They do not rob, they do not pillage, they just go on, from the foot of the Balkan Mountains, from the frontiers of Transylvania, through Hungary. On foot, on horseback, on wagons, in close columns, on they go, silently, homewards.

With them goes hope, and Károlyi watches with an anxious eye : if he turned back, if he lifted his fist... And Roumanian heads in sheepskin caps appear above the crests of the mountains, look after the Germans, and their feet stamp on Transylvania's heart.

My bitterness overflowed and I burst out, " We shall take it back ! "

The Transylvanian women pressed my hand.

" We shall take it back, " said one of them; " I do not know how, but I feel it will be so. "

As I came out of the house I saw my brother Béla come towards me. He said hurriedly, " I met Emma Ritoók, who also is in despair. She asked me to tell you that she must speak to you. " That again reminded me that probably there were many of us, only we did not know of each other... My mother, my brothers and sisters, Countess Zichy, the Transylvanian women, Emma Ritoók, they are faces I can see, voices I can hear, but beyond them there must be many women scattered in the great silent multitude, left to themselves, who weep over the past and fear the future...

When the electric tram stopped I stepped forward to get off. Somebody knocked me in the back. My feet missed the steps and I fell, face first, into the road. I looked back. It was a fat young man, in brand-new field uniform. His characteristic nose fell like a soft bag over his lips. He jumped over me without saying a word, nor did he attempt to help me. He was in a hurry... I just caught sight of his two fleshy ears under his cap as he rushed on.

That is typical of the streets of Budapest to-day; in fact that is the only reason why I mention it. Unfortunately I sprained my ankle.